Detailed Characterization of Hospitalized COPD Patients in Relation to Combined COPD Assessment by GOLD

Li-Cher LOH, Choo-Khoon ONG

DOI10.21767/2572-5548.100004

Li-Cher LOH* and Choo-Khoon ONG

PMC Lung Research, Department of Medicine, Penang Medical College, Malaysia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Li-Cher LOH

Department of Medicine, Penang Medical College

4 Jalan Sepoy Lines, Georgetown, 10450 Penang, Malaysia

Fax: +604 228 4285

Tel: +604 228 7171

E-mail: richard_loh@pmc.edu.my

Received Date: January 04, 2016 Accepted Date: January 12, 2016 Published Date: January 19, 2016

Citation: Li-Cher LOH, Choo-Khoon ONG (2016) Detailed Characterization of Hospitalized COPD Patients in Relation to Combined COPD Assessment by GOLD. Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 1:4. doi: 10.21767/2572-5548.100004

Copyright: © 2016 Li-Cher LOH, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Detailed characterization of hospitalized COPD patients and their clinical outcomes in Malaysia is lacking. Such understanding is important to combat the rising COPD burden.

Patients and Methods: 120 patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation in an urban-based state hospital were consecutively recruited. Comprehensive data on socio-demographics, Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score, clinical parameters, healthcare experiences and hospital outcomes was prospectively collected from medical records and interviews with patients and/or carers.

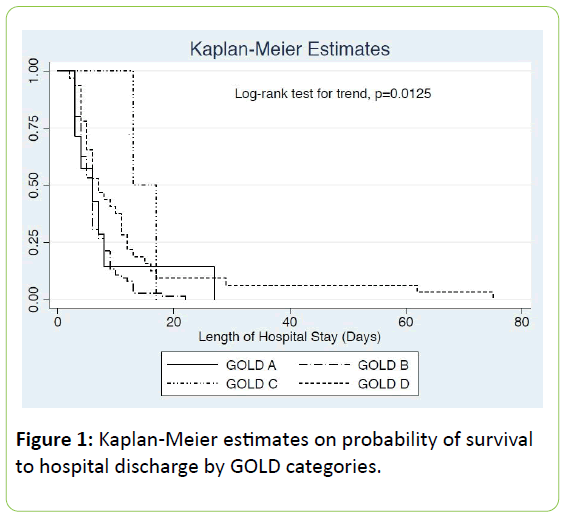

Results: GOLD A, B, C and D categories consisted of 7 (5.8%), 76 (63.3%), 2 (1.6%), and 35 (29.1%) patients respectively. The mean age (SD) was 68 (10.2) years old and 91% were male. Most had only primary school education and low incomes. Most were smokers and frequent exacerbators. About half smoked ≥40 pack years and 10% had ≥5 exacerbations a year. 55% had no comorbidites. The commonest comorbidity was diabetes (20%). 15.8% had previous TB infection. 6.6% had probably ACOS. Over half were treated with inhaled corticosteroids for ≥6 months. Mean BCKQ score was <50%. Anxiety and depression were reported in 14% and 26% respectively. Median length of hospital stay was 6 days. 11.6% had assisted ventilation. 3.3% patients died during the hospital stay. Except for Group C, distributions across categories were similar. Multivariate logistic regressions showed that the likelihoods of assisted ventilation and hospital mortality were increased with arterial pCO2 (adjusted OR 2.63, p<0.01) and respiratory rate (1.73, p=0.01) respectively. Kaplan-Meier estimates showed that GOLD categories (p=0.0125 by log rank test for trend), assisted ventilation (p=0.005) and antibiotic administration (p=0.009) were associated with probability of prolonged hospital stay.

Conclusions: Our findings identified the many areas that can be intervened to improve COPD management. GOLD categories as a combined assessment tool of COPD severity are clinically relevant for hospitalized patients.

Keywords

COPD; Hospitalized; GOLD; Assessment; Malaysia

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading global cause of morbidity and mortality that exacts substantial social and economic burden [1,2]. Its prevalence and disease burden vary across countries and people groups. The World Bank/WHO Global Burden of Disease Study has ranked COPD as the seventh most common cause of premature death in Malaysia for 2010 [3]. In collaboration with Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) initiative, we have recently estimated the COPD prevalence at 3.4% in a suburban population of Malaysia [4].

In a population-based survey of Asia-Pacific countries [5], over half of the interviewed COPD patients from Malaysia reported ≥one exacerbation in the past twelve months and many experienced negative impact on work and activities. The Malaysia figures were among the highest in the survey. A qualitative study of local COPD patients and doctors showed a consistent theme of poor patient knowledge, compromised psycho-social and physical functioning, and lacking confidence to self-manage [6].

Although national guideline for COPD management has been available since 1999, prescribing of long-acting betaagonist and enrolment onto pulmonary rehabilitation programme remained low [7]. The national management guideline has since been updated in 2009 [8]. Hospitalized patients with COPD studied in one local state hospital had poor quality of life with one-fifth reported exacerbations of more than twelve times a year [9].

A detailed characterization of hospitalized COPD patients and their associated hospital outcomes can provide a broad insight into how COPD is impacting local patients and a sampling of how COPD is being managed in Malaysia.

Since 2011, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has recommended a combined assessment tool to assess disease severity, health status impact and exacerbation risk in order to guide therapy [10].

We conducted a prospective study that comprehensively characterized COPD patients hospitalized for exacerbation in our local hospital and reviewed them according to the GOLD combined assessment approach.

Patients and Methods

In an observation study, all consecutive patients with COPD admitted to respiratory wards of an urban-based 1200-bed state teaching hospital were prospectively recruited over a three-month period (January to March 2013). Included were all new or old patients diagnosed with COPD according to GOLD (reference to GOLD) admitted for an exacerbation.

The study formed part of a larger COPD study approved by the National Research and Ethics Committee (NNMR Research no: 3998).

Data collection

Data collection was carried out using a standardized questionnaire. The data was collected by face-to-face interview (after obtaining verbal consent from patient and/or relatives) and from medical records.

They consisted of comprehensive social and demographic details (including living spouse and young children at home), known COPD risk factors (including indoor biomass burning and previous pulmonary tuberculosis), clinical details prior to admission (including previous clinic FEV1, prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), comorbidities and COPD Assessment Tool (CAT) score [11]), breathlessness scores by modified Medical Research Council Scale (mMRC) [12], patient knowledge of COPD by Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire [13], psychological status by Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS) [14], details on healthcare experience (i.e. admission hours, weekend or weekday admission), clinical parameters on arrival, doctors’ interventions (i.e., antibiotic administration and assisted ventilation) and clinical outcomes (hospital death and length of hospital stay).

The diagnosis of probable ACOS is based on history of physician-diagnosed asthma and/or positive family history of asthma alone. Carlson’s comorbidity index that estimates the risk of death is used to grade comorbidity severity [15].

Combined COPD assessment

Patients were categorized into Group A, B, C and D according to GOLD 2011 recommendation of a combined, multi-dimensional assessment approach [10].

The cut-off point between high and low risk of future exacerbation is based on FEV1 of 50% predicted normal or previous reported exacerbations of three times a year.

In the latter, we chose three instead of two because of the generally high reported exacerbation rates among our cohort and that the difference between these two cut-off points is probably clinically irrelevant [16]. In our categorization, previous reported exacerbation rate is preferable to FEV1 due to missing prior FEV1 information from most patients. The cutoff point between the “more” or “less” symptoms follows the GOLD recommendation of CAT of 10 and MRC of 2 (whichever is higher).

Statistical analysis

Data is shown as GOLD categories of A, B, C and D for comparison. Continuous data is described as mean and standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. Categorical data is described in number and percentage.

Continuous and categorical data are analyzed by student ttests and chi-square tests respectively for differences in hospital all-cause mortality and requirement for assisted ventilation.

Variables with a p value of <0.2 are included for simple and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Hosmer-Lemeshow test is used to ensure that the variables fit the models. Kaplan-Meier estimates are used to examine for associations of GOLD categories (log-rank test for trend) or other variables with length of hospital stay (log rank test). A p value of <0.05 is considered as statistical significant.

Results

A total of 120 patients were recruited and interviewed. Data were collected as completely as possible for all patients.

GOLD categories and socio-demographic characteristics

Majority of patients fell into Group B followed by Group D. There were only 7 (5.8%) and 2 (1.6%) in Group A and C respectively. The mean age was 68 years old. Most were from the age group of 60 to 79 years old. Almost all were male. While most had healthy BMI, about a quarter to near half were either underweight or overweight in every category.

About a tenth were obese. Over two-thirds were married and lived with children and/or siblings. Less than 10% had young (5 years or under) children at home. Most had only primary school education.

About a quarter had none or secondary education. Near 50% had income less than RM1000 a month. The distributions of these characteristics were generally similar across all GOLD categories (Table 1).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Total | |

| N (%) | 7 (5.8) | 76 (63.3) | 2 (1.6) | 35 (29.1) | 120 (100) |

| Mean age (SD), yrs | 60 (8.9) | 68 (9.5) | 63 (3.3) | 68 (11.7) | 68 (10.2) |

| Age groups | |||||

| <60 yrs | 4 (57.1) | 17 (22.3) | 0 (0) | 9 (25.7) | 30 (25.0) |

| 60-79 yrs | 3 (42.8) | 51 (67.1) | 2 (100) | 19 (54.2) | 75 (62.5) |

| ≥80 yrs | 0 (0) | 8 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (20.0) | 15 (12.5) |

| Male | 7 (100) | 68 (89.4) | 2 (100) | 33 (94.2) | 110 (91.6) |

| *BMI (n=82) | |||||

| Underweight | 1 (25.0) | 10 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 9 (33.3) | 20 (24.3) |

| Healthy | 2 (50.0) | 25 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 9 (33.3) | 36 (43.9) |

| Overweight | 1 (25.0) | 11 (22.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | 17 (20.7) |

| Obese | 0 (0) | 4 (8.0) | 1 (100) | 4 (14.8) | 9 (10.9) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 6 (85.7) | 58 (76.3) | 2 (100) | 24 (68.5) | 90 (75.0) |

| Single | 1 (14.2) | 7 (9.2) | 0 (0) | 8 (22.8) | 16 (33.3) |

| Widowed/ divorced | 0 (0) | 11 (14.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.5) | 14 (11.6) |

| People lived with | |||||

| Spouse only | 0 (0) | 15 (19.7) | 0 (0) | 7 (20.0) | 22 (18.3) |

| Children/ siblings | 6 (85.7) | 48 (63.1) | 2 (100) | 21 (60.0) | 77 (64.1) |

| Alone/ nursing home | 1 (14.2) | 13 (17.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (20.0) | 21 (17.5) |

| Having < 5 yrs old children at home | 1 (14.2) | 9 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 11 (9.1) |

| Education level | |||||

| None | 1 (14.2) | 19 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 10 (28.5) | 30 (25.0) |

| Primary school | 2 (28.5) | 34 (44.7) | 2 (100) | 16 (45.7) | 54 (45.0) |

| Secondary school | 4 (57.1) | 20 (26.3) | 0 (0) | 9 (25.7) | 33 (27.5) |

| College/ University | 0 (0) | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.5) |

| Income per month | |||||

| <RM1000 | 1 (14.2) | 33 (43.4) | 1 (50.0) | 22 (62.8) | 57 (47.5) |

| RM1000-3000 | 5 (71.4) | 32 (42.1) | 1 (50.0) | 10 (28.5) | 48 (40.0) |

| RM3001-5000 | 1 (14.2) | 6 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (5.8) |

| >RM5000 | 0 (0) | 5 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.5) | 8 (6.6) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; BMI=Body Mass Index; RM=Malaysian Ringgit

Note: Figures shown are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified. * Data collected was fewer than 120.

Table 1: Patients’ social and demographic characteristics.

Exposure to COPD risk factors

Majority were ex-cigarette smokers. Only 4% never smoked. Near half smoked ≥40 pack years of cigarettes. About a quarter had exposure to indoor biomass burning. The distribution was similar across GOLD B and D categories (Table 2).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Total | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 1 (14.2) | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (4.1) |

| Current | 2 (28.5) | 14 (18.4) | 1 (50.0) | 5 (14.2) | 22 (18.3) |

| Ex | 4 (57.1) | 59 (77.3) | 1 (50.0) | 29 (82.8) | 93 (77.5) |

| Cigarette pack years | |||||

| Zero | 1 (14.2) | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (4.1) |

| 20-Jan | 2 (28.5) | 6 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.2) | 13 (10.8) |

| 21-39 | 3 (42.8) | 23 (30.2) | 0 (0) | 17 (48.5) | 43 (35.8) |

| ≥40 | 1 (14.2) | 44 (57.8) | 2 (100) | 12 (34.2) | 59 (49.1) |

| Exposure to Indoor biomass burning | 3 (42.8) | 14 (18.4) | 0 (0) | 10 (28.5) | 27 (22.5) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

Note: Figures shown are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified.

Table 2: Exposure to COPD risk factors.

Patients’ clinical characteristics prior to admission

Mean CAT score was 21 out of 40. Overall mean (SD) mMRC score was 2.4 (0.89) out of 5. FEV1 were only available in about half the patients. The mean FEV1 (SD) was 0.9 (0.30) litres and 42 (13.8)% predicted normal. About half had prior COPD exacerbations of 1 to 2 times a year. About 10% had ≥five times of exacerbations a year. 13% were first-time exacerbators. The distribution across the GOLD categories reflected these characteristics since they were delineated along these criteria (Table 3).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Total | |

| *CAT (n=113) | 8.7 (1.25) | 21.1 (6.06) |

N/A | 25.1 (6.10) | 21.8 (6.71) |

| *mMRC, (n=115) | 1.6 (0.81) | 2.2 (0.78) | 3 (0) | 3.0 (0.83) | 2.4 (0.89) |

| *FEV1 (litres) (n=64) | 1.2 (0.39) | 0.9 (0.26) | N/A | 0.7 (0.33) | 0.9 (0.30) |

| *FEV1 (% pred) (n=61) | 61.6 (23.45) |

42.5 (11.40) |

N/A | 39.9 (15.64) | 42.7 (13.80) |

| *COPD exac/yr (n=117) | |||||

| None | 2 (28.5) | 14 (18.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (13.6) |

| 2-Jan | 5 (71.4) | 59 (79.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 65 (55.5) |

| 4-Mar | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (100) | 21 (61.7) | 24 (20.5) |

| ≥5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (35.2) | 12 (10.2) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; CAT=COPD Assessment Tool [mean (SD) score]; FEV1=Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second [mean (SD)]; COPD exac/yr=number of COPD exacerbations in the past 12 months

Note: Figures shown are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified. * Data collected was fewer than 120.

Table 3: Patient’s clinical characteristics prior to admission.

Patient’s comorbidities

Most patients had Carlson Comorbidity Index at zero. About half had no comorbidity while about a third had only one. Overall 15.8% had previous TB infection and a fifth had diabetes mellitus. About 6.6% had probably ACOS. Over half had prescribed ICS over 6 months especially those in Group D. Otherwise these distributions were fairly similar across all GOLD groups (Table 4).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Total | |

| Carlson CI | |||||

| Zero | 5 (71.4) | 42 (55.2) | 1 (50.0) | 19 (54.2) | 67 (55.8) |

| One | 1 (14.2) | 25 (34.2) | 0 (0) | 9 (25.7) | 36 (30.0) |

| ≥Two | 1 (14.2) | 8 (10.5) | 1 (50.0) | 7 (20.0) | 17 (14.1) |

| Number of comorbidity | |||||

| None | 4 (57.1) | 38 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 15 (42.8) | 58 (48.3) |

| One | 3 (42.8) | 27 (35.5) | 0 (0) | 13 (37.1) | 43 (35.8) |

| Two | 0 (0) | 9 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (17.1) | 15 (12.5) |

| ≥Three | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (2.8) | 4 (3.33) |

| Previous TB | 1 (14.2) | 11 (14.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (20.0) | 19 (15.8) |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 13 (17.1) | 1 (50.0) | 11 (31.4) | 25 (20.8) |

| Probable ACOS | 0 (0) | 6 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | 8 (6.6) |

| * Daily use of ICS (n=97) | |||||

| None or < 3 months | 3 (60.0) | 11 (18.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.4) | 16 (16.4) |

| 3 to 6 months | 1 (20.0) | 11 (18.6) | 1 (50.0) | 6 (19.3) | 19 (19.5) |

| 6 to 12 months | 1 (20.0) | 21 (35.5) | 1 (50.0) | 5 (16.1) | 28 (28.8) |

| > 12 months | 0 (0) | 16 (27.1) | 0 (0) | 18 (58.0) | 34 (35.0) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; Carlson CI=Carlson Comorbidity Index; ACOS=Asthma COPD Overlap Syndrome; ICS=Inhaled Corticosteroids

Note: Figures shown are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified.

Table 4: Patient’s comorbidities.

Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ)

Overall mean BCKQ score was less than 50%. More in Group D had <50% score while more in Group A and B had >50% score (Table 5). This reflects an overall poor knowledge of COPD among the patients and worse in Group D (Table 5).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n=6) |

B (n=69) |

C (n=1) |

D (n=32) |

Total (n=108) |

|

| Mean scores (SD) | 23 (13.0) | 29 (11.0) | 30 (0) | 26 (10.0) | 28 (10.9) |

| Mean % (SD) | 35 (20.0) | 45 (17.0) | 46 | 41 (15.4) | 43 (16.7) |

| Low % score | 4 (66.6) | 45 (65.2) | 1 (100) | 26 (81.2) | 76 (70.3) |

| High % score | 2 (33.3) | 24 (34.7) | 0 | 6 (18.7) | 32 (29.6) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

Note: Figures shown are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified. *Full score is 65 points. Low or high % score is based on 50% cut-off point

Table 5: Bristol COPD knowledge questionnaire*.

Healthcare experiences, clinical, psychological and laboratory parameters

Over a quarter patients were admitted during weekend and over a third during on-call hours. This reflected the emergency and unscheduled nature of their exacerbations. About a quarter reported depressions according to HADS while a smaller proportion (14.7%) were anxious. Arterial blood gases and oxygen saturation results on initial admission were fairly normal (recorded with or without oxygen supplement). Mean respiratory rate and pulse rate were 25 and 100 breaths/beats per min respectively. Mean temperature was 37.4°C. Mean blood pressure was in normal range. Mean blood white cell count, urea and sodium were also in normal range. All these distributions were fairly similar across all GOLD categories (Table 6).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Total | |

| Admission day, n (%) | |||||

| Weekday | 4 (57.1) | 50 (65.7) | 2 (100) | 30 (85.7) | 86 (71.6) |

| Weekend | 3 (42.8) | 26 (34.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.2) | 34 (28.3) |

| Admission time, n (%) | |||||

| Normal hrs | 2 (28.5) | 53 (69.7) | 1 (50.0) | 20 (57.1) | 76 (63.3) |

| On-call hrs | 5 (71.4) | 23 (30.2) | 1 (50.0) | 15 (42.8) | 44 (36.6) |

| *HADS, n (%) (n=88) | |||||

| Borderline anxiety | 0 (0) | 10 (18.5) | - | 9 (31.0) | 19 (21.5) |

| Anxiety | 2 (40.0) | 5 (9.2) | - | 6 (20.6) | 13 (14.7) |

| Borderline depression | 1 (20.0) | 5 (9.2) | - | 11 (37.9) | 17 (19.3) |

| Depression | 0 (0) | 13 (24.0) | - | 10 (34.4) | 23 (26.1) |

| Arterial blood gas | |||||

| * pH (n=113) | 7.34 (0.55) | 7.36 (0.07) | 7.31 (0.13) | 7.36 (0.10) | 7.36 (0.08) |

| * pO2, kPa (n=112) | 11.4 (5.37) | 11.4 (4.59) | 7.4 (3.60) | 15.9 (18.90) | 12.6 (10.93) |

| * pCO2, kPa (n=113) | 7.0 (3.41) | 5.6 (1.94) | 7.6 (2.26) | 5.9 (2.21) | 5.8 (2.14) |

| * HCO, mmol/L (n=112) | 26.6 (4.76) | 24.7 (4.90) | 26.4 (2.61) | 24.3 (5.52) | 24.7 (5.03) |

| Oxygen % saturation | 93 (7.4) | 93 (6.0) | 77 (9.8) | 93 (5.5) | 93 (6.3) |

| *Respiratory rate (n=105) | 23 (1.8) | 24 (4.7) | 28 (0) | 26 (5.0) | 25 (4.7) |

| *Pulse rate (n=119) | 100 (13.8) | 98 (21.4) | 129 (26.8) | 103 (22.6) | 100 (21.7) |

| Temperature °C | 37.2 (0.83) | 37.4 (1.20) | 38.0 (0.35) | 37.4 (0.48) | 37.4 (1.01) |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||

| Systolic | 126 (17.8) | 135 (24.8) | 151 (26.8) | 127 (21.6) | 132 (23.8) |

| Diastolic | 81 (15.8) | 79 (13.0) | 89 (4.2) | 77 (13.5) | 79 (13.5) |

| Blood parameters | |||||

| *wbc (n=115) | 10 (5.5) | 13 (6.0) | 11 (3.1) | 14 (6.1) | 13 (6.0) |

| *urea (n=115) | 4.2 (2.57) | 5.6 (2.70) | 13 (11.59) | 6.6 (5.63) | 5.9 (4.03) |

| *sodium (n=115) | 137 (4.6) | 135 (5.5) | 137 (3.8) | 136 (5.1) | 135 (5.3) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; mMRC=modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score; wbc=white cell count in 109/L

Note: Figures shown are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified; * Data collected was fewer than 120. pO2and oxygen % saturation was recorded with or without oxygen supplement. Blood urea and sodium were in mmol/L.

Table 6: Healthcare experiences, clinical, psychological and laboratory parameters during initial hospital admission.

Interventions and clinical outcomes

Most patients had antibiotic prescribed. Median length of hospital stay was 6 days. Assisted ventilation was needed in 11.6% (9.1% invasive and 2.5% non-invasive). 4 (3.3%) patients died during the hospital stay (Table 7).

| COPD GOLD Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Total | |

| *Antibiotic (n=119) | 2 (28.5) | 62 (81.5) | 1 (100) | 27 (77.1) | 92 (77.3) |

| LOS | 6 | 6 | 15 | 7 | 6 |

| Assisted ventilation | |||||

| None | 6 (85.7) | 70 (92.1) | 0 (0) | 30 (85.7) | 106 (88.3) |

| Invasive | 1 (14.2) | 4 (5.2) | 2 (100) | 4 (11.4) | 11 (9.1) |

| Non-invasive | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (2.5) |

| Death | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.5) | 4 (3.3) |

Abbreviations: COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; Antibiotic=antibiotic administered on admission; LOS=length of hospital stay (median days) excluding death cases.

Note: Figures shown are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified; * Data collected was fewer than 120.

Table 7: Interventions and clinical outcomes.

Associations with hospital all-cause mortality and assisted ventilation

Respiratory rate and arterial pO2 (in preference to oxygen saturation) were selected to enter into logistic regression analysis. Simple logistic regression showed that both were associated with increased likelihood of hospital mortality. Multivariate logistic regression showed that only respiratory rate was associated with increased likelihood of hospital mortality after adjusting for each other (Table 8).

| Odd Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

| Hospital mortality | ||||

| Respiratory rate | 1.53 (1.15-2.03) | <0.01 | 1.73 (1.09-2.74) | 0.01 |

| Arterial pO2 | 1.42 (0.96-2.03) | 0.05 | 1.83 (0.81-4.13) | 0.14 |

| Assisted ventilation* | ||||

| On-call hours admission | 3.65 (1.13-11.7) | 0.02 | 2.83 (0.35-22.51) | 0.32 |

| Arterial pCO2 | 2.65 (1.74-4.04) | <0.01 | 2.63 (1.48-4.65) | <0.01 |

| Blood bicarbonate | 1.19 (1.06-1.32) | <0.01 | 0.97 (0.80-1.18) | 0.82 |

| Respiratory rate | 1.15 (1.03-1.28) | <0.01 | 1.12 (0.92-1.37) | 0.22 |

| Blood urea | 1.16 (1.03-1.29) | <0.01 | 0.97 (0.79-1.17) | 0.76 |

Abbreviations: CI= 95% confidence interval

Note: * includes both invasive and non-invasive ventilation; pH is not tested in preference for pCO2 for logistic regression (whether crude or adjusted). Oxygen % saturation is not tested in preference for pO2 (whether crude or adjusted).

Table 8: Logistic regression for hospital all-cause mortality and assisted ventilation.

Admission during on-call hours, arterial pCO2 (in preference to arterial pH), blood bicarbonate, respiratory rate and blood urea were selected to enter into logistic regression analysis. All showed association with increased likelihood of assisted ventilation based on simple logistic regression. After adjustment for one another, only pCO2 was associated with increased likelihood of assisted ventilation (Table 8).

Association between GOLD categories with length of hospital stay

Kaplan-Meier estimates showed that probability of prolonged hospital stay is increased with GOLD categories (p=0.0125 by log rank test for trend) [Figure 1], assisted ventilation (p=0.005 by log rank test) and antibiotic administration (p=0.009 by log rank test). GOLD categories remained near statistical significant (p=0.057) after adjusting for assisted ventilation and antibiotic administration.

Discussion

Our findings described a wide range of illness behaviors and clinical features in hospitalized patients with COPD exacerbations. Many of these illness behaviors represented opportunities for intervention to improve COPD management. Importantly, GOLD categories appear to be clinically relevant in terms of probability of survival to hospital discharge. These GOLD categories have been introduced in 2011 guidelines as a combined, multi-dimensional assessment tool for COPD severity to guide therapy [10]. This is intuitive given that COPD has multiple symptomatic effects to contribute to its severity [17].

It is obvious that the choice of symptom measure (mMRC vs. CAT) will influence category assignment. In a Korean cohort of COPD, a CAT score of 10 was most concordant with an mMRC score of 1, not 2 [18]. In a Spanish cohort, up to 25% of the patients could be re-categorized when these two scores were applied separately [19]. We followed the GOLD recommendation of assigning the category according to the higher score of the two systems. We based our exacerbation risk on previous exacerbation rate of 3, not 2 because of the overall high rates of reported exacerbations among our patients. This will arbitrarily increase the threshold for Group C and D and increase our patient number in Group A and B.

Consistent with other studies, Group C was also the least prevalent in our cohort [20-22]. In fact, our Group C had only two patients and was therefore too few to allow meaningful interpretation. The larger Group B and D simply reflected our COPD cohort that was symptomatic and undergoing exacerbation. Unlike others [23], we did not observe any biological differences or differences of comorbidity prevalence in our patients. This is likely due to our smaller cohort size compared to other studies. A large observational study of Europe and US had identified that ICS was frequently overprescribed in Group A and B patients [22]. Similarly, more than half our Group B patients were prescribed ICS for over six months. This is likely due to the common practice of indiscriminate prescribing of ICS to all diagnosed with COPD and the general availability of fixed but not separate ICS and long-acting beta-agonist inhalers.

There have been conflicting results with regards to prediction of mortality by GOLD categories [21,24]. Our findings did not support this. However we showed that GOLD categories could predict the probability of survival to hospital discharge. Antibiotic administration and assisted ventilation were two additional factors that were shown to reduce the probability of hospital discharge in our cohort. Prolonged duration of antibiotic therapy and use of specific antibiotic class have been shown to predict in-hospital treatment failure [25]. Our findings showed that the association with COPD categories remained significant even after adjusting for these two factors. To our knowledge, there has been no published study looking at the association of GOLD categories with inpatient hospital discharge. Our finding may be novel and suggest another prognostic use of the GOLD categories.

Our multivariate analyses showed that respiratory rate and arterial pCO2 were independently associated with an increased likelihood of hospital mortality and assisted ventilation respectively. These are recognized prognostic indicators of respiratory distress and failure [26,27]. Interestingly, arterial pO2 was associated with increased likelihood of hospital mortality from the simple logistic regression. Pre-hospital, high concentration oxygen therapy during acute exacerbation of COPD has been associated with increased mortality [28]. This is because of the potential of aggravating respiratory acidosis by inadvertently high oxygen therapy during ambulance transport. Our finding may support a need for such caution in our local setting when patients were arriving with COPD exacerbation.

Most of our hospitalized COPD patients were elderly, smokers, married and lived with children and/or siblings. Most had low income and education level. These generally reflect the socio-demographics of the patients’ generation in Malaysia and the type of patients who sought treatment in government-sponsored hospital. The huge pack years of cigarette smoked and prevalence of indoor biomass exposure are also a reflection of an older age group and generation that used such means of cooking in Malaysia. The high degree of breathlessness, poor health-related quality of life and frequent exacerbations in our cohort may represent a more severe COPD disease that were not adequately addressed or treated in many of our patients. Such frequent exacerbation rates were also reported in other studies involving Malaysia [4,5]. The small number of first-time exacerbators indicates that hospitalized setting is not the ideal place to diagnose COPD early. Diabetes, and not cardiovascular disease, was the commonest comorbidity in our cohort. This observation may be due to the particular high prevalence of diabetes in Malaysia [29]. The prevalence of ACOS appears low at 6% compared to the estimated prevalence between 15 to 55% globally [30,31]. A poor knowledge of COPD among our COPD patients is consistent with the other Malaysian study [6] and reflects an important lack of public and patient education of COPD in Malaysia. There were a significant proportion of anxiety and depression reported in our cohort especially Group D patients. These psychological disorders are wellrecognized major comorbidities in COPD that can bring on poorer prognosis [32,33]. All these findings identify areas that we can intervene to improve COPD treatment in our local patient population.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the Penang Hospital Director and Director-General, Ministry of Health Malaysia for the support and approval of this research.

References

- Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. (2006) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. EurRespir J;27: 397-412.

- Mathers CD, Loncar D (2006) Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med; 263: 436-437.

- Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) profile: Malaysia (2015).

- Loh LC, Rashid A, Siti S, Gnatiuc L, Patel JH, et al. (2016) Low prevalence of obstructive lung disease in a suburban population of Malaysia: A BOLD collaborative study. Respirology.

- Lim S, Lam DCL, Muttalif AR, Yunus F, Wongtim S, et al. (2015) Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Asia-Pacific region: the EPIC Asia population-based survey. Asia Pac Fam Med; 14: 4.

- Wong SSL, Abdullah N, Abdullah A, Liew SM, Ching SM, et al. (2014) Unmet needs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a qualitative study on patients and doctors. BMC FamPract; 15: 67.

- Azarisman SM, Hadzri HM, Fauzi RA, Fauzi AM, Faizal MP, et al. (2008) Compliance to national guidelines on the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Malaysia: a single centre experience. Singapore Med J; 49: 886-891.

- Malaysia National Guidelines for COPD Management (2015).

- Loh LC, Lai CH, Liew OH, Siow YY (2005) Symptomatology and health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med J Malaysia; 60: 570-577.

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Updated 2016) by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, et al. (2009) Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. EurRespir J; 34: 648–654.

- Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, et al. (2004) The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med; 350: 1005-1012.

- White R, Walker P, Roberts S, Kalisky S, White P (2006) Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ): Testing what we teach patients about COPD. ChronRespir Dis; 3: 123-131.

- Bjellanda I, Dahlb AA, Haugc TT, Neckelmannd D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J Psychosomatic Res; 52: 69–77.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis; 40: 373-383.

- Schmidt SA, Johansen MB, Olsen M, Xu X, Parker JM, et al. (2014) The impact of exacerbation frequency on mortality following acute exacerbations of COPD: a registry-based cohort study. BMJ Open; 4:e006720.

- Jones PW (2001) Health status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax; 56: 880-887.

- Rhee CK, Kim JW, Hwang YI, Lee JH, Jung KS, et al. (2015) Discrepancies between modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score and COPD assessment test score in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis; 10: 1623–1631.

- Rieger-Reyes C, García-Tirado FJ, Rubio-Galán FJ, Marín-Trigo JM (2014) Classification of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity according to the new Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2011 guidelines: COPD assessment test versus modified Medical Research Council scale. Arch Bronconeumol; 50: 129-134.

- Han MK, Mullerva H, Curran-Everett D, Dransfield DT, Washko GR, et al. (2013) GOLD 2011 disease severity classification in COPDGene: a prspective cohort study. The Lancet Respir Med; 1: 43-50.

- Soriano JB, Alfajame I, Almagro P, Casnova C, Esteban C, et al. (2012) Distribution and prognostic validity of the new GOLD grading classification. Chest; 143: 694-702.

- Vestbo J, Vogelmeier C, Small M, Higgins V (2014) Understanding the GOLD 2011 Strategy as applied to a real-world COPD population. Respir Med; 108: 729-736.

- Agusti A, Edwards LD, Celli B, Macnee W, Calverley PM, et al. (2013) Characteristics, stability and outcomes of the 2011 GOLD COPD groups in the ECLIPSE cohort. EurRespir J; 42: 636-646.

- de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, Divo M, et al. (2014) Prognostic evaluation of COPD patients: GOLD 2011 versus BODE and the COPD comorbidity index COTE. Thorax; 69: 799-804.

- Cristafulli E, Torres A, Huerta A, Guerrero M, Gabarrus A, et al. (2015) Predicting in-hospital treatment failure (=7 days) in patients with COPD exacerbation using antibiotics and systemic steroids. COPD; 9: 1-11.

- Chang CL, Sullivan GD, Karalus NC, Mills GD, McLachlan JD (2011) Predicting early mortality in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using the CURB65 score. Respirology; 16: 1461-1451.

- Yang H, Xiang P, Zhang E, Guo W, Shi Y, et al. (2015) Is hypercapnia associated with poor prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? A long term follow-up cohort study. BMJ Open; 15: e008909.

- Austin MA, Wills KE, Blizzard L, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R (2010) Effect of high flow oxygen on mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in prehospital setting: randomized controlled trial. BMJ; 341:c5462.

- Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Shetty AS, Nanditha A (2012) Trends in prevalence of diabetes in Asian countries. World J Diabetes; 15: 110-117.

- Marsh SE, Travers J, Weatherall M, et al. (2008) Proportional classications of COPD phenotypes. Thorax;63:761-767.

- Weatherall M, Travers J, Shirtcliffe PM, et al. (2009) Distinct clinical phenotypes of airways disease de ned by cluster analysis. EurRespir J;34:812-818.

- Hanania NA, Mullerova H, Locantore NW, et al. (2011) Determinants of depression in the ECLIPSE chornic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort. Am J RespirCrit Care Med; 183: 604-611.

- Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, Cao Z, Ong KC, et al. (2007) Depressie symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med; 167: 60-67.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences